How COVID-19 is remaking the economy – Article written by Mark Ludlow, Queensland bureau chief in the AFR July 6, 2020.

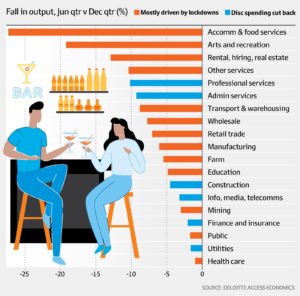

Australia’s recovery from the recession caused by the global pandemic really will be a mixed bag.

While the coronavirus lockdowns and border closures took a wrecking ball to the economy, especially the tourism and services sector, the road back from COVID-19 will not be consistent for all industries or states.

The Deloitte Access Economics Business Outlook report confirms the economic recovery from the coronavirus will be like a game of snakes and ladders for different sectors as they attempt to return to “normal” activity.

The mining sector, which has formed the backbone of Australia’s economic success over the past decade, continues almost unabated, as a resurgent China keeps buying iron ore and coal.

But for other sectors, such as tourism, education and retail, there are many companies that are clinging to survival – a point that will not be lost on Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg when they decide whether to extend the JobKeeper payments past September.

Australia’s relative success at containing the coronavirus – the recent outbreak in Victoria notwithstanding – has come at a high economic cost: the first recession in 30 years.

The driver for many industries – strong overseas population growth, international travellers and overseas students – has been choked off (possibly until mid-next year), forcing many enterprises to rethink their business models.

As the Deloitte report notes, “no migrants, no momentum”.

“That flow of migrants is now all but turned off. That hurts tourism and education immediately, and it also weighs on the recovery, affecting everything from housing construction to the utilities,” it said. “And these effects will linger.”

Here is a snapshot of how the pandemic is reshaping the economy, sector by sector.

Tourism

The tourism industry has been “ground zero” for the coronavirus-induced economic recession.

The summer of bushfires, the closure of national and state borders, and the coronavirus lockdowns have destroyed the industry, which takes in accommodation, travel agents, restaurants and cafes.

While some restaurants and cafes were able to pivot to takeaway, the strict COVID-19 restrictions meant many outlets simply shut for the bulk of the three-month lockdown.

“Businesses unable to adapt found themselves facing an uncertain future,” the Deloitte report found.

The easing of restrictions and planned opening of Queensland’s borders on Friday have provided a glimmer of hope. The beaches of the Gold and Sunshine Coast have begun filling again during school holidays, albeit mostly with Queenslanders rather than interstate travellers.

“There is still hope for activity in the sector to return to pre-pandemic normality. Forecasts show a significant rebound in economic activity for the sector over the period from 2021 to 2023,” Deloitte said.

But in regions such as Cairns and North Queensland, which were highly dependent on international travellers, including China – Australia’s number one market which delivered $12 billion a year – many shopfronts remain boarded up.

The recent flare-up in cases in Melbourne, and the closure of the NSW-Victoria border from midnight on Tuesday, will have an ongoing drag on the sector.

For now, the tourism and travel industry is hoping a domestic tourism resurgence and a trans-Tasman bubble will kickstart the ailing sector. International tourism seems too far off on the horizon and isn’t expected to return until mid-2021 at the earliest. – Mark Ludlow

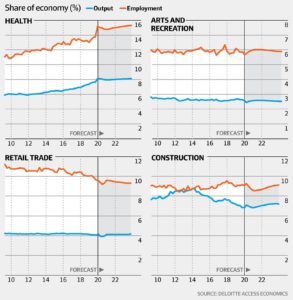

Retail

The $300 billion retail sector enjoyed record monthly sales growth in May due to pent-up demand and government stimulus underpinning spending, but the gains are not expected to last.

Retailers are worried sales will “fall off a cliff” at the end of September if JobKeeper subsidies unwind as planned and mortgage and rent holidays come to an end.

The retail sector was struggling even before the coronavirus crisis, with weak wages growth, high household debt and soft consumer confidence crimping demand.

The COVID-19 crisis has amplified those factors. Unemployment is expected to reach 8.2 per cent in 2020-21, according to Deloitte forecasts. Household incomes have taken a massive hit from job losses and fewer hours worked, and could take years to fully recover, wages growth is expected to come to a standstill and house prices are falling.

While consumer confidence, as measured by the Westpac-Melbourne Institute, rebounded in May after falling to the lowest levels since the 1990s recession in March, pessimists still outnumber optimists and recurrent outbreaks will keep consumers anxious.

While the food and grocery sector will continue to do well, demand for clothing and accessories is likely to remain weak if consumers continue to spend more time at home. At some stage, shoppers will also exhaust opportunities to refurnish their homes, overhaul their gardens and undertake DIY projects, so the homewares, furniture and hardware sectors will come back to the pack.

Another factor likely to crimp retail sales growth over the next few years is population growth. Population growth has accounted for about 50 per cent of real retail sales growth over the last the last decade but if borders stay closed net migration (which has accounted for about two-thirds of population growth) is expected to plummet over the next two years. – Sue Mitchell

Construction

The sharp drop-off in residential construction looming later this year and beyond as projects are completed earned itself a chilling moniker in the industry: the valley of death.

The thought of thousands of tradies out of work and the flow-on effect into the rest of the economy was high on the agenda for the federal government as it put together what became the HomeBuilder package in early June, in an effort to stimulate the construction market.

The pipeline of housing development was contracting even before the pandemic hit. Tough times don’t just mean new home buyers are less likely to make a move. The coronavirus has also closed the immigration pipeline, which for so long has underpinned the health of the property sector.

By mid-2021, as the report notes, the population will be about a quarter of a million people fewer than had been expected.

That’s bad news for both housing and commercial construction. Exacerbating the situation is the squeeze on credit for developers. The slowing economy will also make local investors more wary about funding new construction projects.

If there’s a brighter note in the construction sector, it’s the pipeline of public infrastructure investment, much of it major road and rail projects centred on Sydney and Melbourne.

“The continuity of the existing pipeline is essential to Australia’s recovery from this recession,” Deloitte said. – Nick Lenaghan

Health

Healthcare is supposed to be one of the sectors most resilient to an economic downturn, but the pandemic challenged that long-held assumption.

The Deloitte report revealed the sector would experience a “one-off upwards blip” in 2020, taking up a larger share of the country’s total economic activity and employment. But the health of the industry has not been uniform and many segments of the sector have been on life support.

Dentists, physiotherapists, private hospitals, surgeons and even some medical device makers saw revenue fall off a cliff overnight after COVID-19 hit.

Global bans on elective surgeries throughout March and April resulted in 80 per cent-plus drops in sales for medtech businesses such as Cochlear and Stryker, while at the other end of the spectrum ResMed upped production of ventilators.

For drug and device makers doing clinical studies, these also ground to a halt, causing massive year-or-more delays and triggering additional costs.

Even biotech giant CSL, which has held up well against the downturn and is helping the University of Queensland bring its COVID-19 vaccine candidate to life, hasn’t escaped the claws of the pandemic. Its recruitment for a phase one study on a gene therapy for sickle cell anaemia has been slow, due to COVID-19.

But the healthcare businesses that have been affected most from the pandemic are still expected to recover strongly, buoyed by an increased focus on health and wellbeing, said Deloitte.

The industry can also expect a boost from additional government funding for health infrastructure in the aftermath of the pandemic, with Deloitte suggesting the country should invest in its own healthcare manufacturing capabilities.

“We think it makes sense for the federal government to own some health manufacturing capacity within Australia, so that it can be more readily used as surge capacity.” – Yolanda Redrup

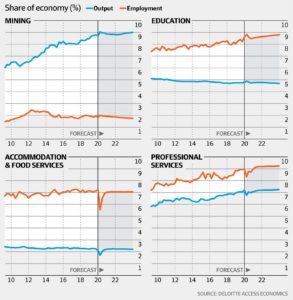

Professional services

The professional services sector has been hard hit by clients cutting back on external advisers due to the pandemic.

Output from the professional services industry grouping, which includes architects, accountants, lawyers, engineers, marketers, consultants, veterinarians and economists, shrunk by about 10 per cent between the end of 2019 and mid-2020, according to the report.

“This sector relies heavily on the wider Australian economy and had been growing steadily in the months leading up to COVID,” the report notes.

“However, just as broader levels of employment and economic activity have plummeted, so too has the health of this industry. And, as cost pressures bite, companies have cut back on their use of external advisers, leading to a drop in demand for professional services and a slowdown in industry output.”

Deloitte Access Economics notes the pandemic has hit consultants the hardest.

“The pandemic has had a different and varied impact on each sub-sector here, with consulting and advisory services hit hardest. An uncertain economic environment has motivated business clients to re-evaluate their financial priorities, causing them to delay some projects or cancel them altogether,” the report notes.

The slowdown has caused the big four consulting firms, Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG and PwC, to put in place wide-scale cost-cutting measures, including cuts to staff pay and partner profit share, to offset the difficult market conditions. (Deloitte Access Economics is a division of Deloitte.)

This has included large job losses across the firms, with Deloitte cutting more than 700 roles, PwC cutting 400 and KPMG cutting 200.

A separate estimate by British-based research firm Source Global Research forecast the Australian consulting market is set to contract by about 13 per cent to $US5 billion ($7.4 billion) due to the pandemic.

The situation is even worse for “discretionary” consulting services, such as change management. Source estimated that demand could fall by as much as 40 per cent for this type of advice. – Edmund Tadros

Mining

The closure of state borders at the height of lockdowns put miners in a difficult position. The “flying in” part of fly-in-fly-out was suddenly problematic. Of much greater concern for the companies was what a global recession would do to their order books.

Despite the uncertainty, pockets of the mining sector have continued to do well throughout the pandemic, especially where temporary factors have juiced up commodity prices (such as in iron ore).

But how the sector performs from here is inextricably linked to China. Some have warned that Australia’s harder line against the global superpower – asking questions about its role in the pandemic – puts the industry at great risk of trade boycotts.

On this point, Deloitte Access Economics said the threat is “worrying, but not too worrying”.

“It is still very much a case of watch and see. Best guess is that this will mostly be loud talk but only symbolic action – a reverse of Teddy Roosevelt’s ‘speak softly and carry a big stick’,” according to the report.

“That’s because it’s hard for one side to be too difficult for the other in bulk commodity markets. Any pain is mutual.”

The report noted Australia’s high-quality coal was a cleaner option for China, which is grappling with carbon emissions and air quality concerns.

China also depends on Australia for iron ore, and even more so while Brazil and its major producer Vale struggle to provide safe conditions for workers.

Outside of iron ore, world commodity prices are looking a bit sick. Oil especially is in the doldrums, which has thrust Australian LNG producers into unprecedented territory, given the price of gas is linked to crude oil.

Deloitte warned this spelled trouble for the next round of mining investment needed to support longer-term growth prospects. – Brad Thompson

Education

It should have simply been the start of a new, lucrative semester, but in the first few days of March – over a week before the World Health Organisation took the step of calling COVID-19 a pandemic – Sydney University laid out just how bad the outlook was for the $38 billion education export industry.

The uni froze all building works and recruitment as it sought to plug a massive funding shortfall caused by thousands of its international students skipping school. The crisis for Australia’s third-largest export industry has been exacerbated by the war of words with China, a key market for students.

Contact

Get In Touch

We are available to chat just give us a call on 0434 955 417 or 0411 472 213

If you prefer to send an email question/query through the best address is info@peakwm.com.au or simply fill out your name, email address and a short message including your phone number will get back to quickly.